“This bull is testament that age, good genetics, and high-quality habitat can produce truly world-class elk,” he said. “Bull elk of this caliber are incredibly rare in Oregon but it’s great to see that they are still around,” said Penninger, who described the antlers as “jawdropping.” (An animal must undergo a minimum of 60-day drying period before it is officially scored as skulls and antlers will shrink some after their first “green” score immediately after harvest or pick-up.)

Mark Penninger, a certified scorer for Northwest Big Game Records Inc, officially scored the elk in early November after waiting the required 60 days. Certified scorer Mark Penninger with the record Rocky Mountain elk from Catherine Creek Unit. The bull’s skull and antlers were found by a cone collecting crew on private timberland in the Catherine Creek Unit during the summer and turned in to the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife (ODFW). (You will need to register / login for access)Ĭomments below may relate to previous holders of this record.The antlers of a Union County bull elk have been officially scored at 406 6/8 which would make it the second-place record for a typical Rocky Mountain elk in Oregon.

#Biggest elk antlers full#

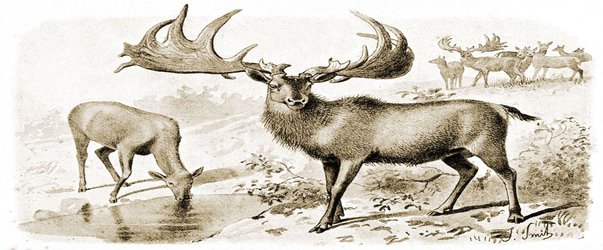

For a full list of record titles, please use our Record Application Search. Records change on a daily basis and are not immediately published online. This compares to the largest antler spread, or "rack", of any living species which was 1.99 m (6 ft 6½ in) from a moose killed near the Stewart River in Yukon, Canada, in October 1897 and now on display in the Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois, USA. The slightly smaller antlers of the broad-fronted stag moose are thought to have reached a maximum breadth of 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) across, tip-to-tip. The upper foot bone alone, which is about 25% more massive than that of a modern moose ( Alces alces, today's largest deer), supported an animal that could exceed 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) in shoulder height and weigh between 900 and 1,200 kg (1,980–2,645 lb). That title goes to the broad-fronted stag moose ( Cervalces latifrons), which roamed across northern Eurasia from the UK to northern Siberia between the late Early and Middle Pleistocene, 1.5–0.21 million years ago. The Irish elk was not, however, the largest deer species ever. A spectacular skeleton discovered in Kamyshlov, east of Yekaterinburg in western Siberia, was recently dated to be just 7,700 years old. Until recently, this huge species was believed to have died out by the end of the Pleistocene epoch, 11,700 years ago, but very early Holocene fossils have lately been revealed on the Isle of Man and in central Europe, confirming that small, scant populations survived the last Ice Age.

Ancient DNA samples from its remains have confirmed that its closest relative was the modern-day fallow deer (traditionally, the elk refers to the moose in British English but in North America it refers to the wapiti, or North American red deer). The Irish elk constitutes one of the most iconic misnomers in palaeontology, being neither an elk nor exclusively endemic to Ireland, in fact widespread from northern Spain to Lake Baikal in southern Siberia between 420,000 and 7,700 years ago. The Latin name of this extinct deer literally translates as “giant antlers”. Based upon fossil evidence of many highly complete skeletons and a few excellent cave paintings, this impressive species is believed to have stood up to 1.8–2.1 m (5 ft 11 in–6 ft 11 in) at the shoulder, and bore enormous palmated antlers in the male that could span up to 3.6 m (11 ft 9.7 in) from tip to tip, and weigh around 40 kg (88 lb).

The largest antlers ever to have evolved belonged to the aptly named giant deer ( Megaloceros giganteus), also known as the Irish elk on account of many fossil specimens having been found in Ireland, and the royal stag in some dated literature.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)